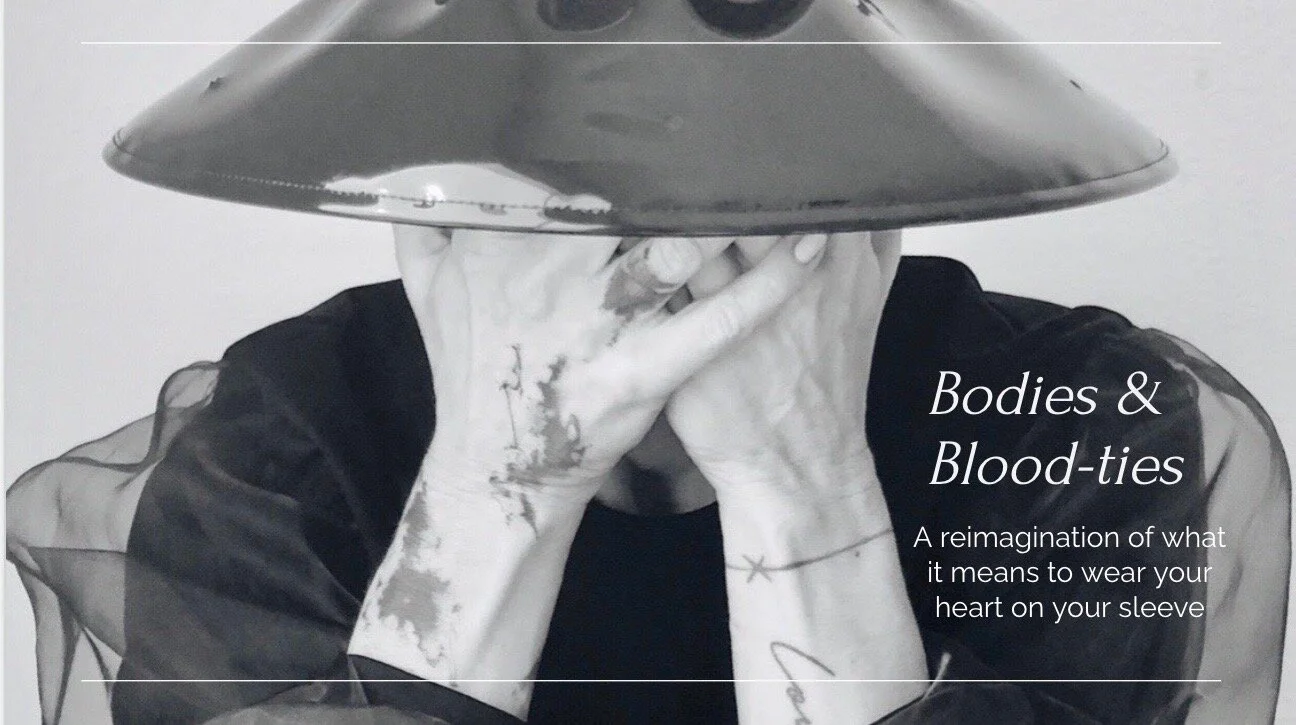

Auto-Ethnography: “Bodies and Blood-ties”

Photograph by: Gillian Davenport | Photograph of: My mother, Mihaela Davenport

Many of my earliest memories involve artwork, in one form or another. My paternal grandmother was a professional artist and an art teacher, and even though she lived in Germany, she made sure to impart some wisdom on me every time she visited. I distinctly remember one of her first visits to my parent’s apartment in Denver where she broke down how to draw the human body anatomically, or the correct way to take on the complicated task of sketching a human face. Additionally, I recall being eight years old and propped into a big leather tattoo-studio chair, waiting patiently for my dad to finish up an eight hour session on his chest. Early on, artwork became the medium through which I not only understood my grandmother, but learned more about my father and the ways in which he chose to adorn his body with the artwork of others. Through a comparative analysis of my parent’s tattoos, my father’s poetry, and my grandmother’s paintings (many of which I only discovered after her death) with the poems, artwork, and tattoos of my own, I have found that many of them are inextricably linked to kinship, and to the act of openly and publicly relating to and claiming one another. My family has been marked by illness, including various kinds of cancer, that has left behind physical and emotional scars. Goldfarb (forthcoming) suggests, “that we examine kinship as a matter of practice,” (11). With this project, I have looked at poetry, artwork and tattoo-ownership as tangible and continuous practices of kinship, of claiming one another and our bodies as our own.

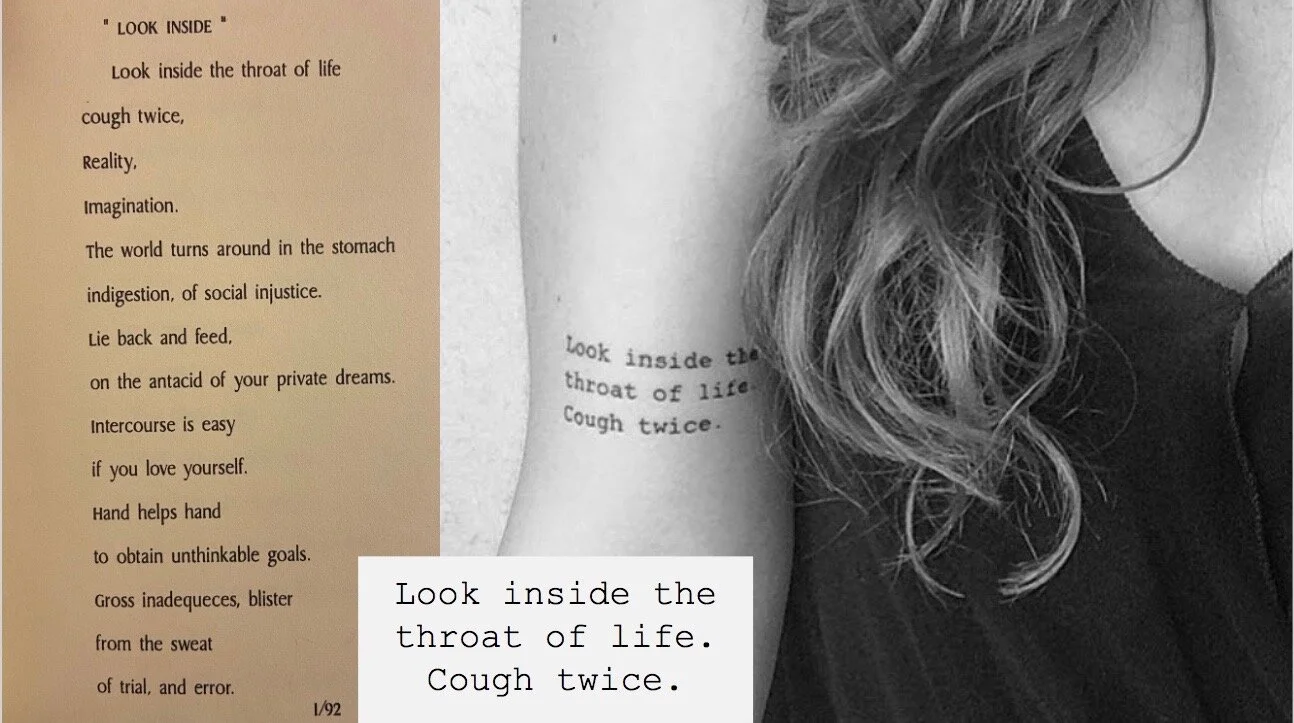

Above: Poem by: My father, Mark Davenport, (January of 1992) |

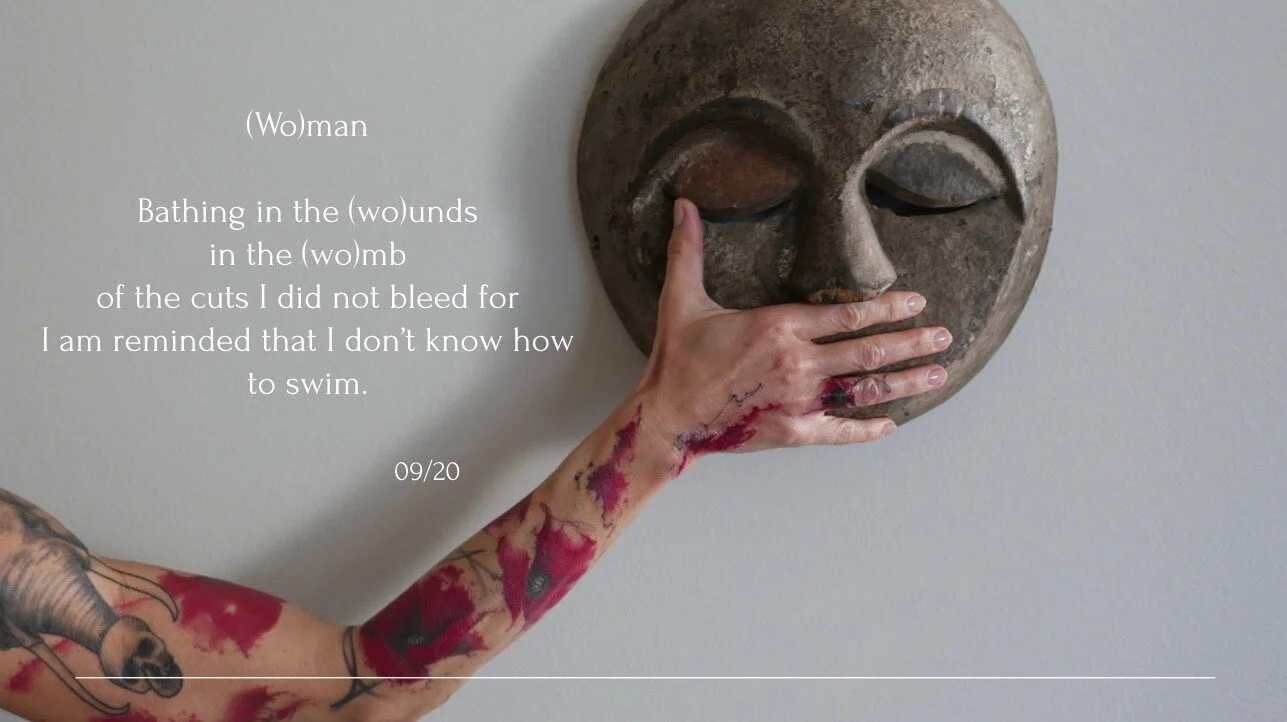

Below: Photograph and poem by: Gillian Davenport (2020) | Photograph of: My mother

Artwork by: Gillian Davenport Photography by: Gillian Davenport | Tattoo on: Gillian Davenport

“For many people, kinship is made in and through houses, and houses are the social relations of those who inhabit them. The significance of what is created and learned in houses also takes us beyond the house.” - Janet Carsten, After Kinship

As a child, I spent a portion of every summer in Romania, in the city where my mother grew up, and I would spend hours watching a dubbed version of the PowerPuff Girls on my grandfather's tiny television. At the time, I spoke little to no Romanian, and many of the memories I have of my grandfather are really of his house. The smell of walnuts and brown sugar, two barking dogs (only one of whom liked children) and a small garden filled with flowers, vines and the occasional snail. When my mother escaped Romania in 1989 (only months before the public execution of dictator Nicolae Ceacescu) she was not able to tell her father that she was leaving, and did not know when, if ever, she would be able to return. While I was working on the drawing above, I decided to include an animal skull, as a sort of homage to my father’s Wyoming heritage. After completing the drawing, I hoped to have a similar image tattooed, but when my tattoo artist asked what kind of flower I wanted to include, I did not reference the peonies in my original sketch. Instead I chose poppies. They remind my mother of the fields of poppies back home. With or without a common language, my grandfather’s house, and presence in my life, shaped me and reinforced my ideas of loyalty, love, and obligation. When I see poppies, I am reminded of the strength of my mother, and of the people that never returned to visit the loved ones they were forced to leave behind.

Photography and artwork by: Gillian Davenport | Tattoo artist: Adam Lunt | Tattoo on: My mother | Man in center photograph: My maternal grandfather, Georghe Man

”Tradition is, at its core, the repetition of cultural practices, the ritualization of the world that continues beyond the individual, even as it is up to each individual to enact it.” - Jason Danely, Aging and Loss: Mourning and Loss in Contemporary Japan

Growing up in a Romanian-American household without any religious presence, we never had many traditions. Sure, my dad and I would make breakfast together every Sunday, or I would go for a walk with my mom on Thanksgiving rather than watch football or eat turkey, but we didn’t consider ourselves a family that had traditions until Mother’s Day of 2016. Filled with the guilt of leaving home to go to college, I wracked my brain regarding what to get my mom for Mother’s Day. She suggested I pay for her first tattoo. As a two-time breast cancer survivor, my mom decided on the words “love heals” as a simple way to intertwine and represent her experiences as an individual and our relationship as a family. My father’s first tattoo, which he got in the early 90's, was in memory of his grandfather. My first tattoo was of my father’s poetry. In one way or another, all of our first tattoos (at different ages, for different reasons, and in different locations) were all linked to kinship, and symbolized our bonds with one another. This tradition continued when my mother then had my artwork (the elephant pictured above) tattooed on her upper-arm. Almost every one of my father’s tattoos related to his family, in one way or another, and his left arm also features a piece of my artwork. Without meticulous planning or official rituals, my family has made it our tradition to commemorate the important moments, and most important people, on our bodies.

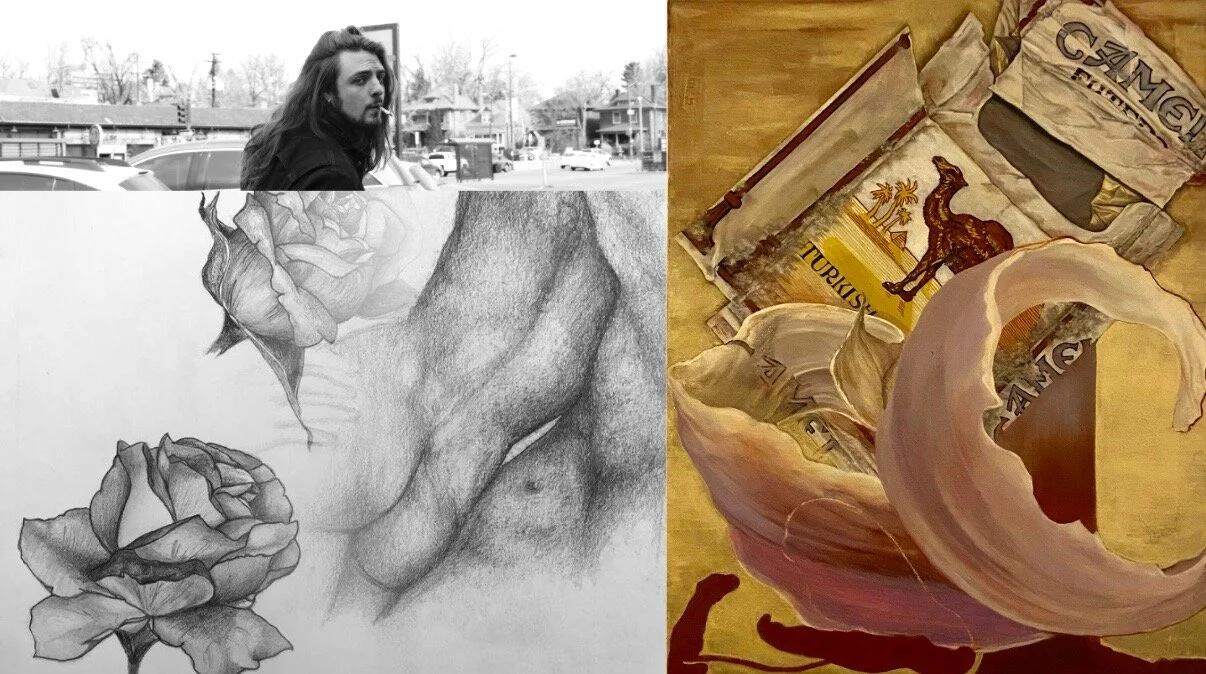

Photograph (left) of: Mark Davenport Photograph (right): Gillian Davenport (age 5), Karen Davenport (my paternal grandmother) and Mihaela Davenport (my mother)

Rose Sketch done by: Gillian Davenport

“Physical characteristics should not be understood as solely biological phenomena, but also as a result of social and cultural dynamics, just as physical characteristics are interpreted and given meaning through social and cultural lenses.” - Kathryn Goldfarb, Fragile Kinships: Child WelFare and Well-Being in Japan

My body, anatomically and genetically, quite literally bears the marks of my family. Having double-jointed shoulders, elbows, hips and knees created an undeniable connection to my father, who is unfortunately-jointed in all of the same ways. As a child, I always found this to be fun, something unique that my dad and I shared, we could bend and crack and stretch in ways that only the other understood. My paternal grandmother, Karen, seemed to think about her own, unique, double-jointed and eventually sick body through her work. A favorite self-portrait of hers included a lizard curved into the shape of an S, with three dry autumn leaves lying next to it. This self portrait, now featured on my father’s calf, was related to her spine. She had scoliosis, which began to cripple her in her later years. My graceful mother and my double-jointed self now have scoliosis as well. In all of the ways I hoped to emulate my mother and grandmother as a child, scoliosis was not one of them, and although my mother and paternal grandmother were not biologically related, their experiences with their bodies and illnesses are hauntingly similar. I wonder if my father’s tattoo-portrait of his mother’s spinal curvature is not only an act of memorialization, but an honoring of shared experiences of both biological and chosen kin, a tribute to unfortunate commonalities.

Above | Photograph and sketch by: Gillian Davenport | Photograph of: My Partner, Patrick Innerst | Oil Painting on canvas by: My grandmother, Karen Davenport

Below | Published poem by: My father, (Allen) Mark Davenport | Photographs by: Gillian Davenport | Photograph of: My mother, Mihaela Davenport

“There is another meaning of en, however, which is, for lack of a better word, somewhat rather magical in its nature and more diffuse in its application [...] In this second meaning, en refers to a seemingly serendipitous encounter and the resultant connection that is however retrospectively characterized as “fated”: en as a play of chance and fate (...)”

- Shunsuke Nozawa, “Phatic Traces: Sociality in Contemporary Japan”

There are certain coincidences in my life that seem too magical not to be fate. For instance, the over thirty-years-old oil-painting of my grandmother’s that has been with me since I moved out of my parents house depicts a pack of Camel Turkish Royal cigarettes, the exact same cigarettes that my long-term partner (who I now consider to be kin) happens to have smoked since we met some six years ago. Other events, like the meeting of a Romanian refugee and a young American from Wyoming in a tanning studio in Nuremberg, Germany, I view less as coincidental and more as very strange and fortunate—maybe even fate. I have grown up in countries and cities that are different from my parent’s hometowns. My first language was my mother’s third, and my father is much more hair-metal than grunge. I think all parents know that their children’s lives will be different than theirs, as Maggie Nelson wrote, “Radical intimacy. Radical difference. Both in the body, both in the bowl” (2015: 86). Radical though it may be, Nelson’s idea of radical difference doesn’t quite capture the differences in my upbringing compared to those of my parents, whether it was life under a communist dictatorship or in rural Wyoming. In a way, our tattoos help us make sense of these radical differences by illustrating our radical intimacy, detailing our own stories (be it via poppies or buffalo skulls) as well as the stories we share. My parents and I all have full sleeves of tattoos. Covered in flowers and faces and memories, we choose to believe in a kinship laced with magic, in the invisible ties that bond us, by blood or by choice or perhaps by something else, to those that we call family. We choose to wear our hearts on our sleeves, placing our innermost selves on the outsides of our bodies and claiming one another as our own. Through poetry and paintings and hours of tattooing, we work to understand this magic—call it love or call it fate—just a little bit more.